Venya Patel converses with Wouter van Noort, journalist from Dutch news organization NRC.

Cities are living ecosystems, though they have long been designed primarily for human needs. Yet, plants and animals continuously adapt, finding niches within our urban landscapes. What if cities were intentionally designed to support not just people, but entire ecosystems?

To explore this idea, we speak with Van Noort who writes about the future of cities, climate, and technology. Through his newsletter and podcast Future Affairs, he examines the challenges of today and their solutions shaping a more sustainable world. In this conversation, we delve into the concept of symbiotic cities—what they are, why they matter, and how they could redefine urban life in the future.

How would you define symbiotic cities?

Symbiosis literally means living together, so strictly speaking every city is symbiotic.

But for me, the term nicely contrasts a way of looking at cities that has become very dominant in recent decades. Let’s call this ‘the lens of separation’: humans and nature in this view are fundamentally separate, and have different interests and needs, humans are positioned outside of and above the rest of the natural world. We have built cities from this point of view: they are the pinnacle of our domination and subjugation of nature, they are powerful machines for controlling natural systems and are optimized for narrowly defined human needs, such as efficient transportation, high rise buildings and consumerism. This is a lens that has come under increasing pressure because of the ecological crises and because of recent scientific findings.

Humans are, of course, nature, and are also very symbiotic by nature: the majority of cells in our bodies are non-human—bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc.,—to name just one basic fact. The idea of symbiotic city, coined by Marian Stuiver, programme leader of Green Cities at Wageningen University, The Netherlands, suggests that a more integrated way of looking at cities and the rest of the living world is possible.

What if we looked at cities from the perspective of bees, or birds, or the mycelial networks in the soil? What if we incorporated ecosystem needs into our built environment? This opens up a range of ideas about urbanism that have tremendous potential for biodiversity, health, and climate resilience.

Why do we need symbiotic cities, and how do they compare to other types of cities?

It is difficult to say, as this is the topic of ongoing research. There is not yet one city that qualifies as a truly symbiotic city. But from research into narrower topics, there is a good deal to say about this.

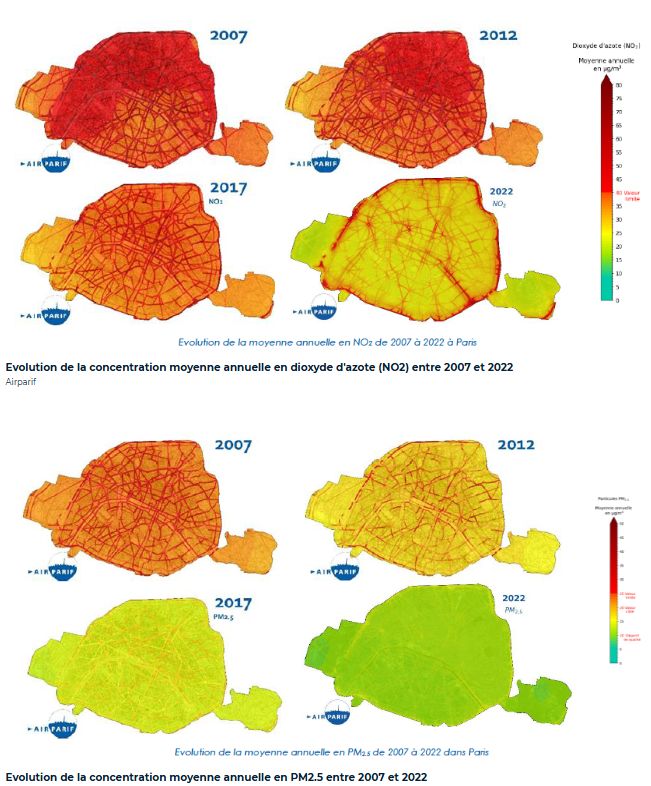

Take the example of Paris, France. Until recently, Paris was plagued by air pollution and smog. In 2014, Mayor Anne Hidalgo took office and radically transformed the city with a focus on sustainability: the Champs-Élysées is being made car-restricted, hundreds of thousands of trees have been planted, numerous facilities have been created for pedestrians and cyclists, various parks and green corridors have been established, and the river Seine has become cleaner and healthier through a comprehensive ecological approach—with significant results.

In other cities worldwide urban green spaces are firmly linked to better outcomes across the board: from mental health to climate resilience, temperature stability, and biodiversity.

How can we design cities that work for animals like pigeons, hedgehogs, or bees, even if we don’t fully understand their perspectives or needs? How might design factor in values of kinship?

We might never fully grasp the experience of other animals and lifeforms, such as plants or trees. But increasingly, science is showing that there is a conscious experience in a wide array of life forms. Probably the closest we can get to really understanding non-human perspectives, is to thoroughly look at fundamental principles in nature: how are ecosystems organized, how do they create resilience and flexibility in nature? There is so much to learn from this ancient intelligence.

Take facade gardens—those tiny patches of greenery that have been popping up on sidewalks in cities lately. It’s becoming increasingly clear that they’re not just cute. A study conducted by Leiden University, The Netherlands, this summer revealed that these tiny green spaces offer surprisingly significant benefits. In just 100 square meters of facade gardens, researchers found 235 plant species and 154 insect species. “It’s an enormous number of species, even more than what is typically found in natural areas,” said researcher Joeri Morpurgo.

The success of these small gardens, I believe, touches on something much bigger. For me, the best book about this is The Darwinian Survival Guide by field biologists Daniel Brooks and Salvatore Agosta. The book revolves around the question: what can we learn from nature about how humanity can survive the coming century? One key takeaway is that to survive, organisms need to be able to move, relocate, and migrate. Once escape routes disappear, so do the options for adapting to changing circumstances. Conservationists, the authors argue, should not focus on restoring nature to some sort of romantic, pristine state. That approach denies the fact that nature is always changing and that healthy ecosystems must be able to adapt to new conditions.

Instead, nature conservation, and city design, should focus much more on enhancing the capacity for change, adaptability, and resilience in the ecosystems that still exist. This means viewing life on Earth as a vast interconnected network that thrives when there are many connections, relationships, corridors, bridges, and escape routes. And what do facade gardens do? They offer islands for urban insects and bridges between those islands, making it easier for them to move around. Are facade gardens enough to halt the dramatic decline of insect populations and other biodiversity? That’s highly doubtful—not on their own, of course. But together, urban gardens can add up to a significant natural area. Especially when combined with greened rooftops, roadsides, dikes, cemeteries, school yards, industrial areas etc.

I find these examples hopeful, especially because they offer tangible actions we can take. At the same time, I can’t shake off the feeling that it’s all still very small-scale and that the forces threatening nature remain far stronger.

What are the values of a symbiotic city? What might be responsibilities for people living in symbiotic cities?

The core is that symbiotic cities need more of a caring ethic than a competitive ethic. I like the Australian philosopher’s Glen Albrecht’s ideas about how society must shift “from the Anthropocene to the Symbiocene”—from a society only focused on humans to one that lives in symbiosis with the rest of nature. Big words, but increasingly, cities and provinces are embracing the idea of integrating more nature into urban spaces. From “green corridors” to “million-tree plans” in many different European cities.

But how can cities truly become more symbiotic? The key, I think is that residents and policymakers need to start thinking in networks rather than silos, in whole systems and complexity rather that the more managerial, top-down, fenced off way of making policy. Not viewing nature as something separate from the built environment, but as something constantly connected to it, fundamental to it—something the city is a part of and cannot live without. Examples of such networks include neighborhood associations that make agreements about the types of greenery planted in gardens and communal spaces, or “plant libraries” with seeds from native species—a small greenhouse where residents can leave plants for their neighbors. Another example is a communal area where people can turn garden waste into usable compost for neighbors, as well as for the insects and plants in the area.

Can you share examples of cities or projects already becoming more symbiotic?

There are so many, for instance, the Rooftop Revolution movement in The Netherlands, that aims to green the vastly underused urban space on rooftops. The facade gardens that are popping up everywhere and are being spurred by all kinds of citizens initiatives. The seed bombs and guerrilla gardening movements. The 3-30-300-rule (stating that every citizen should see at least 3 trees from their windows, should have at least 30% canopy cover in their neighborhood and should have access to a high quality green space withing 300 meters from their house) is developed by Dutch ecologist Cecil Konijnendijk and is being adopted worldwide. Also, ‘sponge cities’ are being developed on many different continents, ‘vertical forests’ are being built in several cities, and the ‘green networks’-approach by the Dutch national forestry organization, is linking nature reserves to inner cities through networks of corridors and stepping stones for biodiversity, like the mandatory nesting stones for birds an bats in new building projects in several European countries. Still, the initiatives are too slow to counter the catastrophic degradation of ecosystems, but something is moving for sure.

What might life be like in a symbiotic city in 2050?

I think I got a nice taste of a potential symbiotic future when I recently visited Rijnvliet in The Netherlands, the world’s first ‘edible neighborhood in the city of Utrecht. It is a unique residential area designed to integrate nature and community through edible greenery, conceived of by residents themselves, who initiated the project and collaborated with agroforestry experts to make it work.

The centerpiece is a park-like food forest featuring apple and pear trees, fruit-bearing plants and shrubs, and herbs. A treetop walkway allows residents to access fruits and nuts easily. Although still developing, the area is expected to resemble a full urban forest within a decade, say food foresters. Beyond the food forest, fruit and nut trees, herb-filled gardens, and vegetable patches can be found throughout the neighborhood. Located near Leidsche Rijn and surrounded by highways, the neighborhood was designed with edible planting as a central feature.

The goal: to create a greener environment, foster community connections, and help residents engage with nature, food, and seasonal cycles—it helps birds and insects and soil quality too, and the early signs are promising. During the neighborhood’s first harvest season, residents were actively picking fruits and sharing tips through group chats and community clubs. Local schools offer food forest lessons, teaching children about edible plants and their seasons.

In September, the community held a market featuring homemade jams and pizzas with neighborhood-grown herbs, and other local products. Resident Kim Hugen, who recently made pesto from foraged greens, told me she appreciated the project’s impact. She even uses calendula from the neighborhood to create ointments. “I’ll need it soon,” she said, gesturing to her pregnant belly. Rijnvliet demonstrates how edible greenery can transform neighborhoods into vibrant, interconnected communities. While still a work in progress, its success shows the potential for urban areas to balance ecological sustainability with community well-being.

Leave a comment