Researchers at UC Santa Cruz, US, recently discovered “nitroplast,” dubbed the “first known nitrogen-fixing organelle” in a eukaryotic cell.

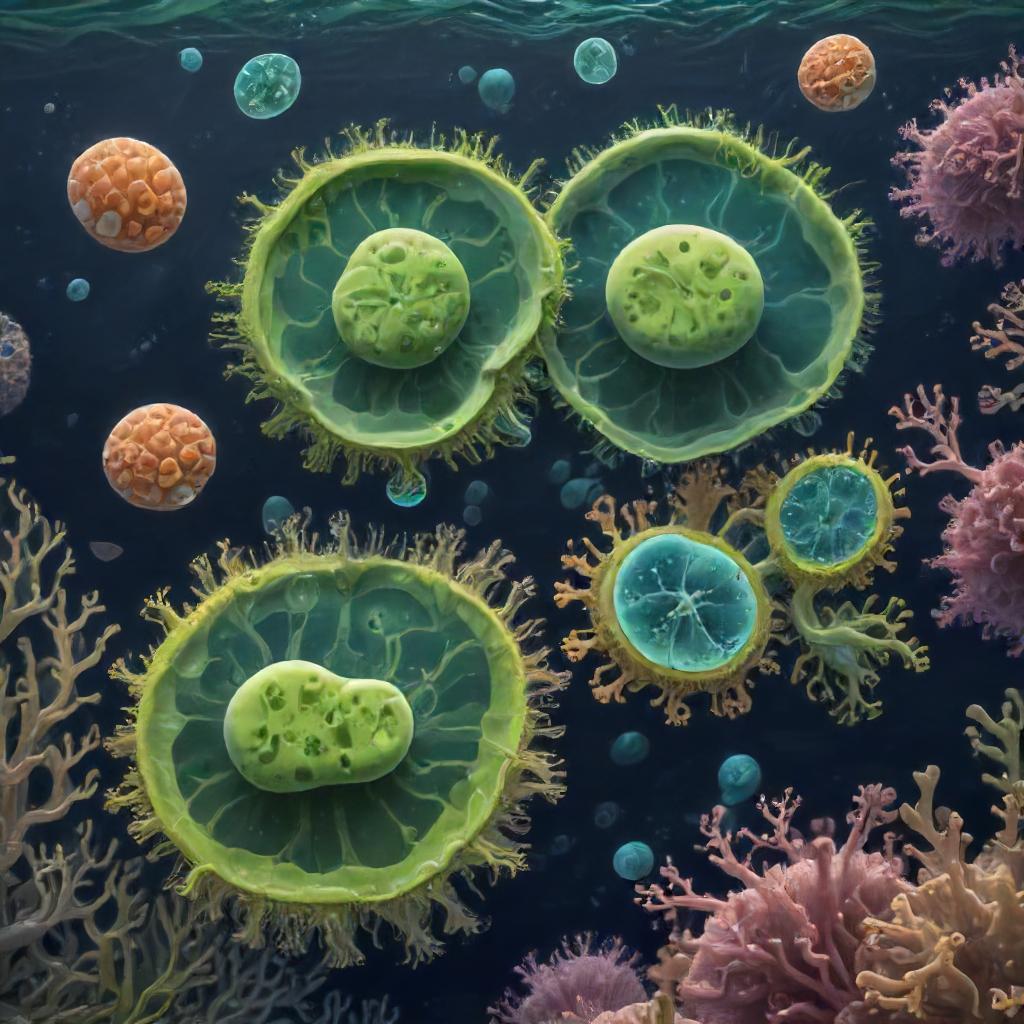

The nitroplast is a result of endosymbiosis, a mutually benefiting relationship where one organism lives in another, evolving beyond symbiosis and into an organelle.

“It’s very rare that organelles arise from these types of things,” says Tyler Coale, a postdoctoral scholar at UC Santa Cruz and first author on one of two recent papers.

“The first time we think it happened, it gave rise to all complex life. Everything more complicated than a bacterial cell owes its existence to that event,” he adds, referring to the origins of the mitochondria. “A billion years ago or so, it happened again with the chloroplast, and that gave us plants.” The third time endosymbiosis occurred, it involved a microbe similar to the chloroplast.

Occurring as the fourth time in the planetary history of endosymbiosis, the nitroplast challenges “modern biology textbooks,” which tell us only bacteria can take nitrogen from the air and convert it for life-use. This is how some plants can fix nitrogen in root nodules by forming symbiotic relationships with bacteria.

All organisms need biologically usable nitrogen, with the new nitroplast being able to fix “significant amounts” of the element from the atmosphere.

Decades of DNA

It all began in 1998, when Jonathan Zehr, a UC Santa Cruz distinguished professor of marine sciences, discovered a short DNA sequence, which appeared to be from “an unknown nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium in Pacific Ocean seawater.”

His team studied this organism and called it UCYN-A.

Meanwhile, at Kochi University in Japan, paleontologist Kyoko Hagino was attempting to culture a marine alga, which turned out to be the host organism for UCYN-A. After 300 sampling trips over ten years, she was able to grow the alga in culture, enabling the study of UCYN-A and its host together.

Initially, the scientists thought UCYN-A was an endosymbiont that was closely related with an alga. However, the two new papers suggest UCYN-A actually co-evolved with its host, going beyond symbiosis and forming an organelle.

Organelle origins

The paper in Cell, published in March, reveals the size difference between UCYN-A and the algal hosts is consistent across the Braarudosphaera bigelowii species. Researchers reveal the exchange of nutrients leads to the growth of the host cell and UCYN-A.

“That’s exactly what happens with organelles,” comments Zehr. “If you look at the mitochondria and the chloroplast, it’s the same thing: they scale with the cell.”

The scientists only confirmed UCYN-A as an organelle until they found how UCYN-A imports proteins from its host cell.

“That’s one of the hallmarks of something moving from an endosymbiont to an organelle. They start throwing away pieces of DNA, and their genomes get smaller and smaller, and they start depending on the mother cell for those gene products — or the protein itself — to be transported into the cell,” continues Zehr.

“It’s kind of like this magical jigsaw puzzle that actually fits together and works.”

The mitochondria and chloroplasts evolved billions of years ago, while scientists say the nitroplast appears to have evolved about 100 million years ago, providing insights into the recent perspective on “organellogenesis.”

Agricultural revolution?

The scientists posit that the discovery has the potential to change agriculture as synthesising ammonia filters from atmospheric nitrogen enabled the course of agriculture and thus the world’s population growth.

The Haber-Bosch process creates about 50% of the world’s food production, however, it also creates 1.4% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Due to this, researchers have been trying to incorporate natural nitrogen fixation in agriculture.

“This system is a new perspective on nitrogen fixation, and it might provide clues into how such an organelle could be engineered into crop plants,” says Coale.

Opinion

Firstly, I would like to clarify that I am not a scientist, though I have great interest in evolution. I see endosymbiosis as a checkpoint—a major mark in Earth’s history of life that has brought about diversity.

I can’t help but wonder what kinds of amazing creatures will the nitroplast bring in the far future.

However, amid the excitement surrounding the discovery of the nitroplast, it is crucial to acknowledge the tendency of humans to seek ways to exploit scientific breakthroughs for their own advantage. History has shown that scientific discoveries often lead to technological advancements that are eventually commercialized or weaponized.

The rush to harness the potential of the nitroplast for agricultural purposes raises ethical questions about the motivations. Are we driven by the desire to address challenges such as food security and environmental sustainability, or are there underlying economic interests at play?

Moreover, possibilities of engineering the nitroplast for agricultural use raises concerns about who stands to benefit from this technology. Will it be accessible to small-scale farmers in developing countries, or will it be monopolised by agribusiness corporations in industrialised nations?

The parallels with the GMO debate are striking. While genetic engineering has the potential to enhance crop yields and resilience, it has also been accompanied by controversies surrounding corporate control, intellectual property rights, and environmental risks.

As we contemplate the implications of the nitroplast discovery, it’s essential to approach it with humility and a recognition of the broader socio-economic dynamics at play. Rather than viewing it solely as a means to optimise agricultural productivity, we should consider equitable and sustainable food systems.

While the discovery of the nitroplast holds promise for addressing key challenges in agriculture, we must be wary of exploiting it.

Written by Venya Patel

Leave a comment